The First Park Visitor Center Celebrating LGBTQ+ History

.

.

“The parks are welcome to everybody – so is our visitor center”

In June 1969, an uprising in response to a police raid on the Stonewall Inn in New York City forever changed the course of the LGBTQ+ movement.

Commemorating the watershed moment, Stonewall National Monument was established as a unit of the National Park System in 2016. The site, considered the birthplace of the modern LGBTQ+ civil rights movement, is now a national monument. The park tells the story of the historic Stonewall Uprising and the movement’s continued legacy.

And on June 28, 2024, the 55th anniversary of Stonewall, a new visitor center will open its doors to the public to further tell the story of Stonewall in the place where history was made.

Diana Rodriguez and Ann Marie Gothard have spent the past six years working with the National Park Service (NPS) to bring that vision to life. As co-founders and leaders of the LGBTQ+ advocacy nonprofit Pride Live, the couple have fundraised for, designed, and are now opening the Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center – which will be the park’s official visitor center – with support from the National Park Foundation (NPF) and other partners.

"The National Park Foundation is honored to have played a role in bringing the Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center to life,” said Will Shafroth, president and CEO of the National Park Foundation. “This groundbreaking addition to the National Park System commemorates the pivotal Stonewall Uprising and serves as a powerful symbol of inclusion and equality. By sharing the stories of the LGBTQ+ community, the visitor center contributes significantly to NPF’s mission to tell the full American story – a story rich in diversity and courageous acts by extraordinary people."

NPF has supported Stonewall National Monument since its 2016 designation, including raising funds to launch the park and supporting various aspects of programming, infrastructure, and partnerships. Most recently, the Foundation has partnered with Pride Live to help fund elements of the new visitor center.

The visitor center will help to preserve and celebrate the legacy of Stonewall, connect park visitors with educational resources, and inspire the next generation to continue the efforts towards equality and civil rights for all.

“The parks are welcome to everybody – so is our visitor center,” Rodriguez says. “Whether you support us or not, I actually hope you do come visit and you learn about the community and you learn about Stonewall.”

‘A Place Where History Was Made’

The visitor center will open at 51 Christopher Street, right next door to the Stonewall Inn at 53 Christopher Street. At the time of the 1969 uprising, the bar occupied both locations, but in the years following, it split into two leases. By signing the lease for 51, Pride Live is reuniting the physical space of the Inn for the first time in over 40 years.

“I think there is something very unique about standing in a place where history was made,” says Rodriguez, founder and CEO of Pride Live. “You can read about history, you can now visually learn about history, but to actually visit the site where history was made, I think is really significant.”

Gothard, chair of Pride Live’s board of directors, remembers seeing the Lorraine Motel at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis as a child and the mark it left on her to visit the place where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. In a similar vein, she hopes the Stonewall visitor center preserves the history of the movement for generations to come.

Indeed, history echoes through the site today. During construction, the crew identified what used to be a walkway that connected 51 and 53 in the Stonewall Inn. It’s since been closed off with bricks but visibly preserved in the visitor center to help visitors feel they’re in the exact physical space where the history they’re learning about occurred.

Stonewall activist Mark Segal was there that night, 55 years ago, when police raided the Stonewall Inn. Today, he’s serving as a senior advisor on the visitor center project. Recently, Rodriguez and her team walked through the soon-to-be visitor center space with Segal.

Segal immediately identified the original Stonewall Inn layout and fixtures. His husband downloaded ‘Age of Aquarius’ on his phone the night before because that’s the song Segal remembers playing throughout Stonewall in the 1960s.

“I turn around and my team is crying, all of them,” says Rodriguez. “It was so emotional to see Mark relive the steps of his youth.”

When Segal was frequenting the Stonewall Inn in the late 1960s, it was a popular gay bar in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. The neighborhood had become a magnet for the LGBTQ+ community and was home to hospitality venues that catered to them, with the Stonewall Inn as one of the most popular. Those bars, restaurants, and clubs were often subject to police raids and would frequently be shut down.

At the time, many aspects of openly living as an LGBTQ+ person were against the law or against policy. People could face criminal prosecution or time in prison or mental institutions for being intimate with same-sex partners, and in New York City, people were often arrested for dancing with or kissing someone of the same sex or for wearing clothes that seemed to be for an opposite gender.

On June 24, 1969, police raided the Inn, confiscated alcohol, and arrested employees. When the Inn still opened the next day, police planned a surprise raid for a weekend night when the bar would be more crowded.

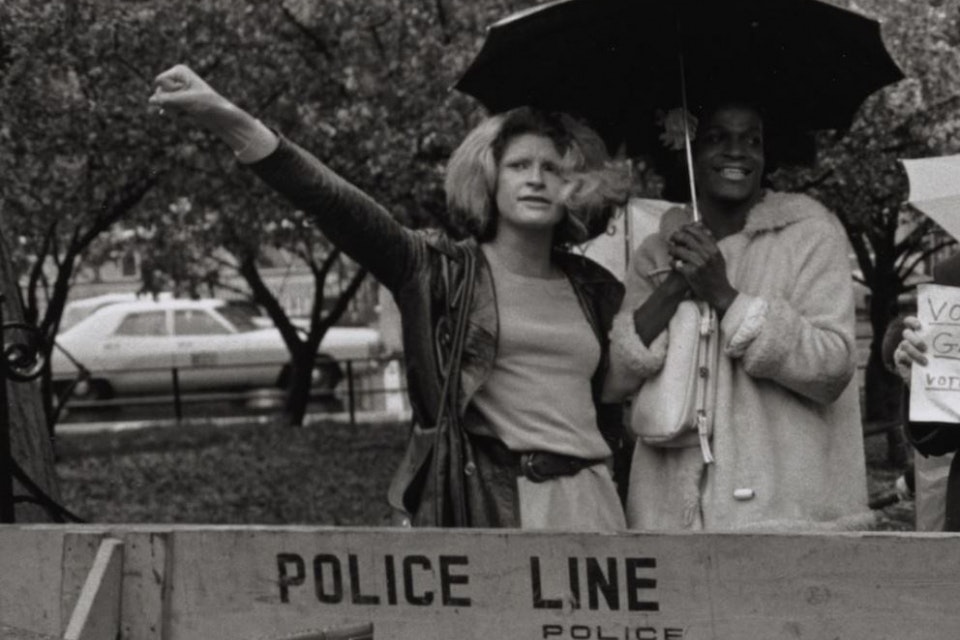

Shortly after 1 a.m. on June 28, undercover police raided the Inn and made arrests. A crowd quickly gathered on the street, some of whom had been in nearby Christopher Park, and began throwing items at officers as they arrested bar patrons. People outside chanted “Gay Power!” and “We Want Freedom!” The situation escalated, and officers locked themselves inside the Inn, while the crowd from outside broke through windows and knocked down the door. The riot ended after a few hours and resulted in 13 arrests and the destruction of the Inn.

For the next week, protestors took to Christopher Park and the surrounding neighborhood each night, with riot police coming to break up the crowd each time.

Stonewall was a flash point for the LGBTQ+ community and activists, first across New York City and then nationwide, launching the modern LGBTQ+ civil rights movement as a national political activist effort across class and other lines. Stonewall galvanized collective protest, group organization, and political engagement at new levels in cities across the country, and more people began publicly showing signs of their sexual orientation.

Activists formed new organizations, including the Gay Liberation Front, Third World Gay Liberation, and Gay Activist Alliance. In a year, the number of LGBTQ+ organizations in the U.S. increased from about 50 to over 1,500.

The physical place of Stonewall still carries symbolism today, and its history continues to inspire the movement and ongoing efforts for equality and civil rights for all people regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Christopher Park – the small park just across from the Stonewall Inn and part of Stonewall National Monument – still serves as a gathering place before marches and parades and a community space to celebrate and commemorate.

A Seed Planted and a Lease Signed

Rodriguez was at the park for the designation ceremony in late June of 2016, just two weeks after the mass shooting at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando.

“The significance of safe spaces for the community, one of which had just been attacked, was an overwhelming feeling during that entire ceremony,” Rodriguez says. When someone planted the seed with her about Pride Live establishing the visitor center for the park, it resonated deeply.

Rodriguez and Gothard began thinking through the key questions: What would it cost? Could they raise enough money? Where would the visitor center be located? What partners would they need? What would opening and operating it entail?

Stonewall National Monument is unique as an urban park. The monument includes 7.7 acres in Greenwich Village, comprised of both public and private property: the private Stonewall Inn; Christopher Park, which is owned by the federal government after it was donated by the City of New York; and parts of city streets. The small park is the only federal-owned part of the site. That means without a visitor center, there’s no indoor space for education and interpretation, no restrooms for park rangers or the public, and no place for programming in inclement weather.

Logistically, a visitor center seemed essential.

“It will mean so much when the visitor center is complete,” Stonewall National Monument Superintendent Shirley McKinney says. “Besides enhancing the interpretive program conducted by our park rangers and providing an additional educational resource for the community and students, our Stonewall rangers will finally have a ‘home.’”

When Gothard visits the park, she often sees parents showing their kids around and explaining the significance of the Stonewall Inn. But as an active bar, the kids can’t go inside and see the space for themselves.

“We’re going to be able to provide a space where people of all generations can go in and experience what it’s all about, and I think that’s just a tremendous gift to be able to give back to our community,” Gothard says.

Beyond that, for married couple Rodriguez and Gothard, the idea of a visitor center held a deeper meaning as well.

“I thought the visitor center was necessary when we started this six years ago. I think over the last six years, here in the United States and abroad, when it comes to the community and other issues, things have not necessarily progressed, and in some cases have gotten worse, including having the most anti-LGBTQ laws on the books ever,” Rodriguez says.

“That's alarming. I don't think a lot of people know what it's like to wake up on Tuesday hoping you have the same rights that you did on Monday.”

Gradually, a few essential puzzle pieces fell into place, the key one being the lease for 51 Christopher Street becoming available from its previous tenant, a nail salon. As part of an urban park in a dense commercial corridor, NPS doesn’t own any buildings in the park footprint, meaning Pride Live had to find commercial space for the visitor center just as any business might.

“With something like this, there is a lot of caution and there is a lot of liability, but when you want something to happen so badly, I think all we saw were green lights,” Rodriguez says. “This was really hard [to fundraise for] because it’s new, and you have to have people believe in it as much as you do.”

Critical partnerships also began to come together. NPS and McKinney have been deep partners on this first-of-its-kind visitor center, which Pride Live will operate through an agreement with NPS.

The ceremonial groundbreaking for the visitor center was held June 24, 2022. From that day, there was a sign at 51 Christopher Street saying the visitor center would open on June 28, 2024.

More recently, Pride Live has been expanding community partnerships and building the support network that will be essential for the urban visitor center and park. Rodriguez and her team have been meeting with local community groups and neighborhood boards to develop relationships as a good neighbor.

As opening day nears, the team is increasingly excited to see the space come to life as a place to spark conversation and inspiration.

“What we hope for the visitor center is a space where anyone can come and just really take a moment and take in the legacy. Understand that you are experiencing this in the space where history happened, and talk about it,” Rodriguez says.

Inside the Visitor Center

The visitor center will share the stories of Stonewall through immersive educational exhibits, art displays, and retail, and will facilitate in-person and virtual tours of the park and lecture series.

The design of the visitor center itself tells a story too. The white space is infused with symbolic colors, that, in the order of the rainbow flag, tell the story of the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement from its beginnings to Stonewall and from today into the future.

“The public can experience consistent and more varied programming of LGBTQ+ history from the riots that started the movement, to the present day,” McKinney says. “From scheduled tours to films, the visitor center will add a dimension of education, programming, and ranger engagement for old and new visitors.”

McKinney looks forward to the visitor center telling the LBGTQ+ story in different mediums in a space dedicated to presenting that history.

“My hope is visitors who don’t know the history will be able to connect on some level with the experience of the LGBTQ+ community,” she says. “We can all connect on a basic level of understanding struggle and overcoming obstacles to fight for what matters most to us, freedom, equality, and being heard.”

A partnership with Parsons School of Design, a prestigious art and design college that also happens to be nearby to the park site, will ensure young voices are reflected in the space through a rotating annual exhibition. The school now offers an elective class that designs an exhibit for the visitor center – students are given the dimensions of the space, and what they create is fully up to them. Last year, with the visitor center under construction, the exhibit was on display at Parsons; this year and in the years ahead, it will be inside the visitor center.

“We want to make sure that young queer and ally voices are represented in the visitor center. … We’ve lived a certain life, and they are living a very different life,” Rodriguez says.

In the back of the space, where the Stonewall Inn dance floor once stood, is a theater that will show video content about Stonewall and host special programs. Pride Live plans to hold events there, including ones that bring people with different opinions together in conversation, and will open the space for community-hosted gatherings as well.

The visitor center will be the place that shares the story of Stonewall – as well as a space for visitors to share their own stories.

“We’re creating immersive experiences,” Gothard says. “If we can have people come through – families, friends, strangers standing next to each other as they’re looking at the exhibits – exchanging stories about what this means to them … this will be the beginning of a lot of storytelling and the preservation of those stories.”

Finally, in addition to being a space for the public, the visitor center will be the home base for park rangers, who for years have used restrooms in neighboring businesses and haven’t had a place that’s their own to store their things or take shelter in bad weather. Rangers will be working in the space, collaborating on research for park programming, starting tours from the visitor center, and coordinating Junior Ranger activities for kids to engage with the park. Visitors will also be able to get their national park passports stamped in the visitor center.

“People don’t necessarily connect the LGBTQ+ community with the National Park Service or the rangers, so for visitors to be able to walk into the space and see that representation is really important: that we can be members of the same family,” Rodriguez says.

Giving Back and Looking to the Future

For Rodriguez and Gothard, the project has been a labor of love and one they are deeply proud of. As longtime national park lovers, being able to partner with NPS has been a “dream come true.”

A few years back, the couple went on a road trip to explore national parks across the country, from Badlands to Yellowstone to Grand Teton National Parks. They had an eye on the visitor experience and what made visitor centers impactful. They also noticed park visitors weren’t always as diverse as America, and they want this new visitor center to fully represent that part of the NPS family – “very diverse, very queer, in the city, very urban,” Rodriguez says.

For Gothard, bringing the visitor center to life has been “the ultimate” way to give back to the LGBTQ+ community and to the public.

“As women, as women of color, as queer women of color, to be able to do something like this, knowing personally the struggles that I’ve had in my own identity and living authentically, I can’t compare it to anything else,” Gothard says. “This is sort of the ultimate in living an authentic life, to be able to stand behind this project, and to do it with the woman that I love.”

The two hope that the visitor center impacts individuals who come to see it and compels them to take action, big or small.

“I hope when people come to visit, they’re able to take it in, they understand the historic partnership that we have with the NPS, they go through all the activations, they go through all the exhibits, they stop at retail, they get their passport stamped, and then as they’ve leaving, it’s affected them such that they want to go and take action,” Rodriguez says.

Be Part of the Past and Future of Our Parks

You can help improve access to places, cultural heritage, and stories that give Americans a stronger connection to our country. Support NPF’s work around preserving the history and culture that live within our national parks.