Remarkable National Park Stories of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders

.

.

Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders have shaped the history of the United States and the world at large for thousands of years, with rich heritage and cultural traditions. National parks across the country highlight the triumphs, perseverance, and contributions of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders and visitors today continue to bring their own experiences and stories to our national parks.

The National Park Foundation (NPF) and our work in preserving history and culture in parks aims to share more comprehensive and inclusive stories that amplify the full range of experiences and voices that are woven into the fabric of the United States, including those of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Join us in exploring a few of these stories told and preserved in national parks.

Instructors at MISLS

Established in 1941 with four instructors and 60 students, the Military Intelligence Language School (MISLS) provided instruction in Japanese reading, writing, interrogation, translation, and interpretation to support the American war effort during World War II. John F. Aiso, a distinguished Harvard-educated lawyer of Japanese descent, was brought in as the director of training. The training provided at the MISLS by Japanese Americans also included the study of Japanese geography, Japanese military organization and technical terms, radio monitoring, and the social, political, economic, and cultural background of the country. The students studied in a converted hangar in Crissy Field, now part of Presidio of San Francisco and Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

With the relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans on the west coast, the school was moved from California to Camp Savage and then Fort Snelling, now part of Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. Throughout the Pacific Theater, 6,000 linguists trained at the MISLS served with distinction. They were so successful that Major General Charles Willoughby once remarked that these language instructors “shortened the Pacific War by two years and saved possibly a million American lives.” In 1946, the school returned to California and eventually became the Defense Language Institute – it is still the U.S. military’s primary language school.

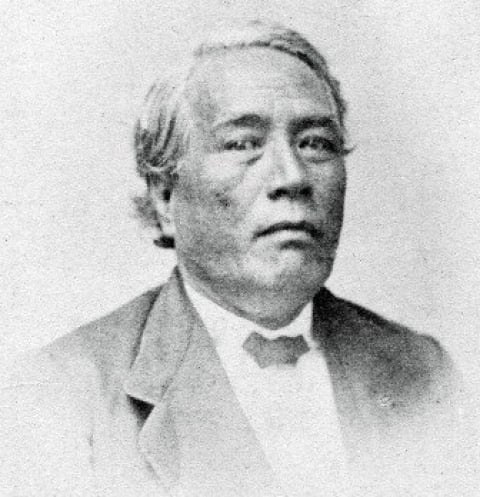

Naukane

Naukane – also known as John Cox (or Coxe) – was one of the many Hawaiians who traveled to the Pacific Northwest to work in the fur trade. A high-ranking member of the Hawaiian royal family, Naukane witnessed the 1779 death of Captain James Cook at Kealakekua Bay at twelve years old.

When the Pacific Fur Company’s (PFC) ship Tonquin arrived in the same bay years later, Naukane was appointed as a “royal observer,” overseeing twelve Hawaiian laborers onboard the Tonquin on a trip to the Northwest. From Fort Astoria, PFC’s primary trading post, Naukane joined British-Canadian mapmaker and surveyor David Thompson on a cross-continental journey with the North West Company.

Amid the breakout of the War of 1812, Naukane was sent to England with a mission to outfit a ship and return to Fort Astoria, which by the time of his 1813 return was renamed "Fort George." In 1814, he returned to Hawai'i and joined the royal court. In 1823, King Kamehameha II and other high-ranking members of the court, including Naukane, traveled to England on a royal visit and tour. Many of the party contracted measles, and those who did not were regarded with suspicion. Naukane then decided to return to his life in the fur trade to escape this scrutiny.

From 1824 to 1842, Naukane worked as a “middleman,” or manual laborer, with the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). He served on boats and even raised over 700 pigs for Fort Vancouver’s farm. He was remembered by many of the residents as a great storyteller, often telling visitors his eye-witness account of Captain Cook’s death. He lived at Fort Vancouver, now preserved as Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, until his death in 1850.

Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu

An immigrant to the U.S. from China, Chien-Shiung Wu contributed to the Manhattan Project and experimental physics. Born in 1912, Wu graduated top of her class with a degree in physics from the National Central University in Nanking, China. After working in a physics lab in China, Wu enrolled at the University of California Berkeley, working under Nobel Prize winning physicist Ernest Lawrence.

In 1944, Wu took a job at Columbia University and joined the Manhattan Project, where her research improved Geiger counters for radiation detection and the enrichment of uranium in large quantities. The work of the Manhattan Project was conducted in numerous places across the country and today, Manhattan Project National Historical Park preserves three of these locations in Tennessee, New Mexico, and Washington.

After World War II, Wu continued to be a leader in physics. She was the first to confirm Enrico Fermi’s theory of beta decay, and the Wu Experiment, which tested the conservation of parity during beta decay, was her design. However, as with many of the contributions women made to science at the time, her work with the experiment was not acknowledged. The project for which the Wu Experiment was designed won physicists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang a Nobel Prize in 1957, but Wu's contributions were not honored. Wu later went on to be elected to the National Academy of Sciences and was the first woman to be president of the American Physical Society and the first person to receive the Wolf Prize in Physics. After her death in 1997, her ashes were buried in the courtyard of her father’s school she attended as a young girl.

Minoru Yasui

Minoru Yasui fought against the exclusion and removal of Japanese Americans during World War II. The first Japanese American member of the Oregon Bar, Yasui was working for the Japanese Consulate in Chicago when Pearl Harbor was attacked. He returned to Oregon, expecting to be called up for service, having been an ROTC cadet in college and commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Reserves after graduating. However, Yasui was turned away nine times as he attempted to report for duty.

In 1942, in defiance of Executive Order 9066, which placed a strict curfew and travel restrictions on certain groups, Yasui walked the streets of Portland, eventually leading to his arrest. Originally sentenced to a year in prison with a fine, Yasui appealed his case. He spent nine months in solitary confinement as his case traveled to the U.S. Supreme Court. Yasui was eventually sent to Minidoka Relocation Center, now Minidoka National Historic Site, where he stayed until his 1944 release. He continued to fight for his case, though it was not resolved until after his death. In 2015, Yasui was posthumously awarded the Medal of Freedom for his work and leadership in civil rights.

The Paniolo

In 1793, Captain James Vancouver presented King Kamehameha I with six cows and a bull, the first cattle to reach the island. Kamehameha put a kapu, or prohibition, on the animals so they would not be hunted or killed, but eventually the cattle population grew so much it became dangerous. So around 1812, Kamehameha permitted the capture of the wild cattle and slowly the beef industry began to grow, especially under the reign of Kamehameha’s son, Liholiho.

Liholiho’s son, Kauikeaouli, heard about vaqueros, or Mexican cowboys, and invited some to Hawaii to teach Hawaiians their methods for cattle ranching. The paniolo, the Hawaiian cowboys, quickly created a distinct culture, crafting their own culture, including styles of saddles, gear, and music. When Ikua Purdy, Archie Kaʻauʻa, and Jack Low competed in a 1908 rodeo in Wyoming, they wore hats adorned with lei pāpale, flower lei, and they defeated some of the best American cowboys on the world stage. Kahuku, now part of Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, was one of the oldest ranches on the island, despite its remote location, rough terrain, lack of water, and volcanic eruptions. Many people in the Kaʻū district where Kahuku sits trace their ancestry to the paniolo who worked in the area.

Tye Leung Schulze

Tye Leung Schulze was a civil rights and community activist, born in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1887. Growing up, Leung and her seven siblings experienced segregation from an early age – local law forced Chinese Americans into separate schools. At twelve years old she escaped an arranged marriage and worked under the tutelage of Donaldina Cameron, a teacher and local activist at the Presbyterian Mission Home.

Leung eventually became a translator and interpreter in court to free Chinese women from sex trafficking, and in 1910 she became the first Chinese woman employed by the federal government, acting as a translator for detained Chinese immigrants.

Notably, Leung became the first Chinese American woman to vote in the U.S. when in 1912 she voted in the presidential primary. Leung was a fixture in the Chinese community in San Francisco as she continued her work as a community activist until her death in 1972. Angel Island Immigration Station, where Leung worked and eventually met her husband Charles Schulze, is a national historic landmark near Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

NPF’s Women in Parks initiative was launched to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which allowed some women the right to vote. Projects and programs supported by the Women in Parks initiative amplifies the voices of women, such as Leung, who made history and continue to shape our future.

Dr. Kazue Togasaki

Dr. Kazue Togasaki was one of the first Japanese American women to become a doctor in the U.S. and delivered over 10,000 babies in her long career. When a 1906 earthquake hit the city, Togasaki helped take care of the wounded in a makeshift hospital, often accompanying Japanese American women as a translator.

Togasaki earned her degree in Zoology from Stanford, finished top of her class in a nursing program at a children’s hospital in San Francisco, yet work was still difficult to find as a Japanese American woman. She attended medical school in Philadelphia and moved back to San Francisco to start her own practice in 1933.

In 1942, the United States government forced 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry across the west coast into internment camps. Togasaki was sent to Tanforan Assembly Center to set up medical facilities to care for her community. Togasaki was moved to several different centers, including Tule Lake and Manzanar relocation centers, providing care and leadership wherever she was. Upon return to San Francisco in 1943, Togasaki reopened her practice and served her community for the next 40 years.

NPF’s Women in Parks initiative supports programs and projects that share the stories of visionary women like Togasaki: trailblazers who dared to imagine a different future. Highlighting the contributions women have made to our country and the role they continue to play in our ever-evolving narrative, Women in Parks projects help NPS share a more comprehensive and inclusive American story.

Jonathan Napela

Jonathan Napela was a prominent na kokua, or helper, at Kalawao in the late 19th century. A descendent of Kuahaliulani, Napela trained as a lawyer and acted as a judge on the island of Maui. He later converted to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and set about translating the Book of Mormon into the Hawaiian language in 1852.

In 1873, Kitty Richardson, Napela’s wife, contracted leprosy and he traveled with her to live at the Kalaupapa Leper Colony on Molokai. Napela was appointed as the superintendent of the leper colony, but due to his unwillingness to enforce a rigid segregation of patients and non-patients, he ran into trouble with the board of health.

In the late 1800s, Hansen’s disease, more commonly known as leprosy, was reaching epidemic proportions on the islands. At the time, there was no effective treatment, no cure, and no knowledge of what caused the disease. Government officials decided isolation was the only answer, setting apart a remote area of land to quarantine those who contracted it to stop the spread of disease. Some people, like Napela, chose to go into isolation with their loved ones as kokua. Today, Kalaupapa National Historical Park serves as a reminder of a nation in crisis and is a place where many families in Hawai'i can reconnect with a relative once considered “lost.”

Leah Hing

Portland-born Leah Hing was the first U.S.-born Chinese American woman to earn a pilot’s license. Born in 1907 in Oregon, Hing took her first airplane ride at a school for Chinese American aviators while on tour with her band, Portland Chinese Girls’ Orchestra.

In 1932, John Gilbert “Tex” Rankin, a national figure in the world of aviation and head of a flying school, met Hing at her father’s restaurant and invited her to “take up flying.” She received her pilot’s license in 1934 from Rankin’s small school based at Pearson Field, one the country’s oldest continuously operating airfields, now a part of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

Hing flew passengers (one at a time in her two-seater biplane!) in the Portland-Vancouver area and became an accomplished and capable flier and in 1939 joined The Ninety-Nines, an organization for women aviators founded by Amelia Earhart. During World War II, Hing worked with the West Coast Civil Air Patrol helping with repairs of navigational equipment and ground training.

After 1941, Hing ended her flying career but remained active in her community. Unable to join Portland’s social club for private pilots and aviation enthusiasts, the Aero Club, because she was Chinese, Hing worked there as a switchboard operator, photographer, and receptionist. She also raised money for the elderly, coached girls’ basketball, and helped immigrants in her community to become U.S. citizens.

Jun Fujita

Jun Fujita was a respected photojournalist, silent film actor, and a talented poet. Born in Nishimura, a village near Hiroshima, Japan, in 1888, he moved from Japan to Canada when he was a teenager and eventually to Chicago, Illinois. Among his many achievements, Fujita worked at the Chicago Evening Post, photographed many noteworthy individuals and significant events such as the 1929 St. Valentine’s Day massacre, was a photographer for Johnson Motors, and published many poems, including poetry written in a minimalist Japanese form called tanka, in prestigious literary journals.

Fujita drew a lot of inspiration from nature. Wildflowers, forests, and different landscapes were often illuminated in his art. In 1928, Fujita and his partner Florence Carr traveled to a remote island near Ranier, Minnesota, which is now part of Voyageurs National Park, and purchased land where Fujita built a rustic one-room cabin, a place to get away from the hustle and bustle of the city. Due to racial and legal inequalities at that time, Carr, a white woman, purchased the cabin on Fujita’s behalf as Minnesota state laws restricted land ownership by Asian immigrants. In addition, while Fujita and Carr were long-time partners, they could not get legally married due to anti-miscegenation laws until 1940.

The cabin that Fujita built on Rainy Lake was reminiscent of Japan’s architecture. It was made of natural materials with a minimalist design and had a side entrance. Complete with floor to ceiling windows, the cabin provided Fujita with magnificent views of the lake and surrounding forest.

In 1996, Fujita’s cabin was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and thanks to NPF’s support, service corps members are restoring the cabin, helping to ensure that more people have the opportunity to learn about Fujita’s life and his important contributions.

These stories are the beginning of the countless lives and histories of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders in our national parks. From George Masa, a photographer and outdoorsman akin to the Ansel Adams of the Smokies, to Wilhelmina Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett, who advocated for Hawaiian women’s right to vote, there are many more stories to discover. We invite you to explore these and other stories preserved in parks as we continue to reflect upon our past, engage with the present, and imagine the future.

Endnote: In this blog post, NPF uses the language Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. While the intent is to honor inclusivity and be representative of various ways that people identify, we recognize that this language does not account for all identities. We recognize the importance and need of specificity in reference to distinct communities. We also recognize that the stories highlighted in this blog post do not account for all identities and we will continue to elevate more stories and help expand the history preserved and shared in national parks.