More than the Stuff of History: Cultural Resources, Expansive Stories, and Finding Meaning in Our National Parks

.

.

They are important not just because they connect us to our past, but also because they connect us to each other, says Megan Springate (she/they).

She’s talking about cultural resources.

Megan works in the National Park Service (NPS) Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education in Washington, D.C., and currently serves as the National Coordinator for the NPS 19th Amendment Centennial Commemoration.

Now you may be asking, what exactly are cultural resources? We asked Megan the same thing.

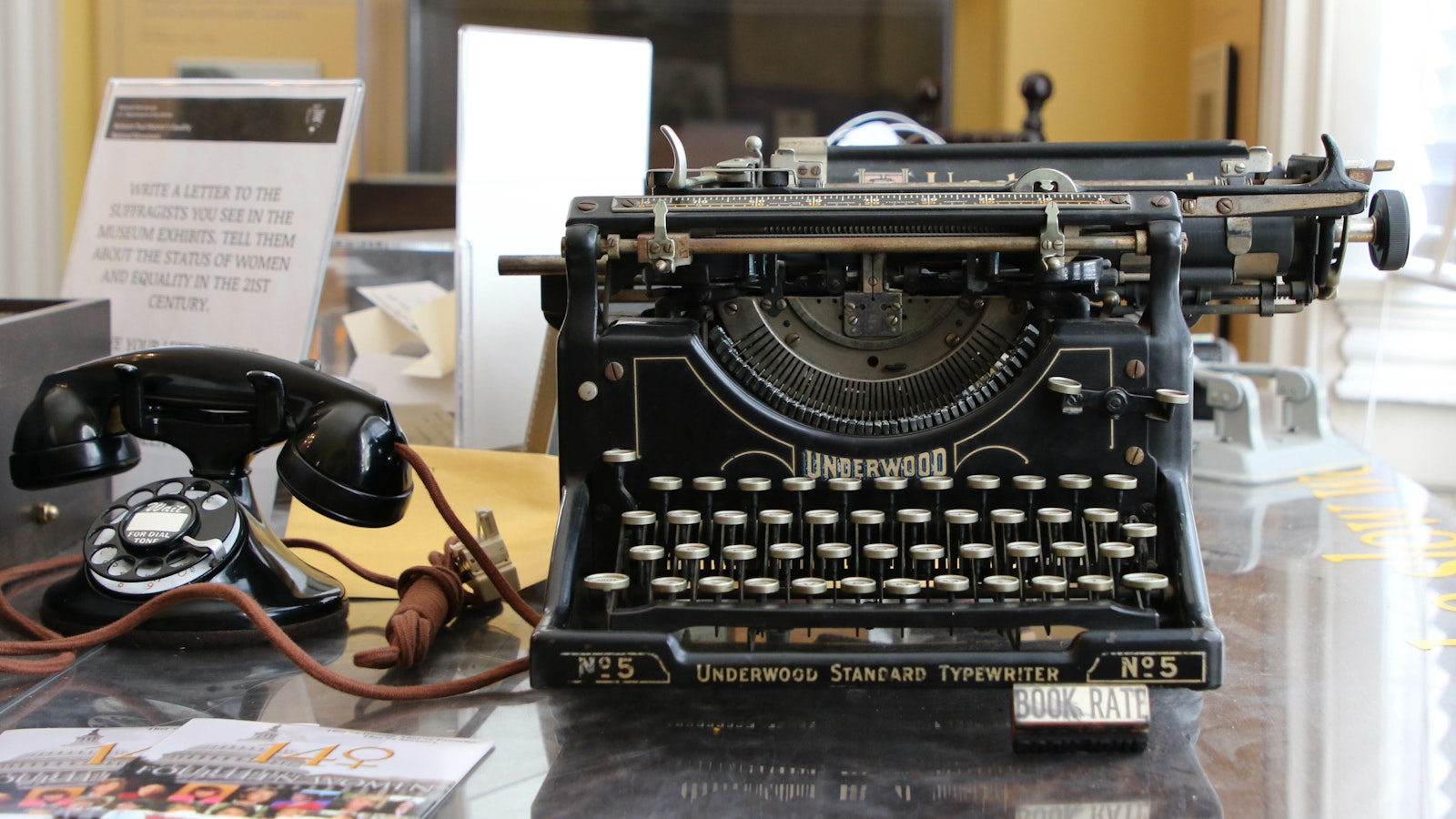

“What first comes to mind for me are tangible things like artifacts, objects, artwork, buildings, and landscapes.” Megan emphasizes that it’s important to note that this definition is based on her perspective as an historical archeologist.

She says items like that can help us learn about the everyday lives of people, the details that may have not been written down. These include things like the choice of dishes and knick-knacks, everyday clothing, what people eat and drink, and household repairs. The objects people use and surround themselves with speak volumes about their lives. She goes on to explain that archaeology helps us better understand the lives of people who haven’t historically been at the forefront of written history, or included at all, like women, the working classes, people of color, and people that were enslaved.

Through her time at NPS and specifically with her work as the editor of the NPS LGBTQ theme study, supported by the National Park Foundation thanks to generous funding from the Gill Foundation, Megan says she’s expanded her understanding of cultural resources to also include what she perceives as being more intangible: Traditional Knowledge*, skills, folklore, and language.

We were honored to have the opportunity to chat with Megan about her personal journey with the national parks community and what she’s learned along the way. We hope you’ll enjoy this glimpse into our conversation.

How would you describe your journey with the national parks community?

Growing up just outside Toronto, Canada, I didn’t visit many U.S. national parks. I vaguely remember once visiting Cape Cod National Seashore when I was very young. But even in Canada, the idea of the U.S. national parks was interwoven in our everyday life. In particular, I remember seeing images of spectacular scenery and also seeing national parks represented in films like Indiana Jones and National Treasure.

I immigrated to the United States in 1999, becoming a citizen in 2010, and in the mid-2000s was working for a commercial cultural resource management company as an archeologist. One of my projects was at the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York – part of Women’s Rights National Historical Park. This work was done before the reconstruction of the chapel. I was deeply moved by the commitment of the NPS employees to the site. The respect, passion, and love they had for their park and its resources was something that you cannot write into a job description. And I remember thinking, “These are the kinds of folks I can work with.” It was that job that planted the seed of possibly working for the NPS.

From 2014 through 2016, I was a contractor with the National Park Foundation as the primary consultant for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer NPS initiative. One of the key results was the completion of LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History. It was the first project ever by a federal agency to examine its LGBTQ+ history and it continues to inspire LGBTQ+ folks, historic preservationists, and community activists to find, preserve, and share their own and their communities’ LGBTQ+ history.

Fast forward to present day, and I’m serving as the National Coordinator for the NPS 19th Amendment Centennial Commemoration. The most meaningful part of my job has been facilitating an NPS-wide working group. Members of this community of practice represent all levels of employment in the NPS, across the country, and in regional offices and programs, as well as National Heritage Areas and other partners.

This group developed a collective vision and goals and continue to collaborate with each other in inventive ways to commemorate the passage of the 19th Amendment, which made it illegal to exclude anyone from voting because of their sex. It is through the work of these folks that the NPS commemoration is committed to sharing the full and complex history of women’s access to the ballot and its legacy, women’s history more broadly, and examining civics and how change is made in our democracy.

My goal is to continue to work for the NPS, connecting undertold and incompletely represented histories to our national story using the places where those histories happened.

What do you personally love about national parks?

I love the diversity of our national parks. There are parks across the country that preserve and celebrate incredible landscapes and the plants and animals that live there. And there are parks across the country that preserve and commemorate pieces of our national history that could otherwise vanish.

Manzanar and Minidoka National Historic Sites preserve the places and histories of confinement camps, also known as internment camps. During World War II, thousands of Japanese Americans were forced from their homes and jobs and confined in these remote camps. It is an ugly part of our history, but one that should not be forgotten.

Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls preserves the places and stories associated with the very first women’s rights convention in the United States. It took place at the Wesleyan Chapel in 1848, generations before the passage of the 19th Amendment and even more generations before the voting rights of so many more were protected in the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of the 1960s.

I love that there are places like Thomas Edison National Historical Park where I can go and learn about scientific and technological advances that changed our world, and Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty where I can walk in the footsteps of the thousands of immigrants that came to the United States for a better life, and Independence Hall in Philadelphia where I stood in the very room in which America was founded.

At Sandy Hook, the part of Gateway National Recreation Area in New Jersey, I have fished, walked the beach, watched the windsurfers, and explored World War II concrete bunkers; on the New York side of Gateway, I have stood in the center of what, when it was built, was the largest parking lot in the world.

I love the endless opportunities, the stories, and the deep connections that are made possible by being in the place where history happened.

Why are cultural resources, in particular, important?

Cultural resources are important not just because they connect us to our past, but because they also connect us to each other.

They invite us to ask ourselves and each other really important questions like: How do we work with all of these different ways of knowing to better understand our world and our histories? What does a culture of respect look like when engaging with intangible and tangible heritage? How do we not center white, middle-class experiences as “normal” and everything else as “other”?

A single object or building or landscape can have many meanings and uses for many different people. Sharing these different perspectives about a shared object or place can help connect us across cultural and societal divides. The arts, an aspect of cultural resources, also allows us to connect with each other, to see the world through different eyes and different experiences.

Why is the 19th Amendment Centennial Commemoration significant to you and what do you hope people will take away from it?

Coordinating the NPS 19th Amendment Centennial Commemoration has special meaning to me on one level because it was while doing archaeology at Women’s Rights National Historical Park those many years ago that I realized the NPS was a meaningful career option for me. This feels like coming full circle.

I feel a responsibility to the people who fought for women’s right to vote to ensure we share an honest history about what that fight looked like, and its legacy.

This is what I want people to take away from the commemoration:

- The passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 was a watershed moment, but let’s be careful not to celebrate it as a “done deal.” We must share the ugly side of the political choices that people made to exclude women of color and immigrants from voting. Thousands of women remained disenfranchised because of their race, cultural affiliation, class, inability to read and write, and incarceration. Keeping these women from the ballot was done both by law and by violence. Leaving out their stories sends the message that these people don’t matter, that their history is unimportant. And that is not how good history or good citizenship works.

- Change in a democracy is messy; history is messy; people are messy. Change happens at the ballot box, in the streets, in the courts, in coffee shops, in living rooms, and in the minds of individuals. And we can all work to make the world a better place – the only thing special about the folks working for change toward the 19th Amendment, or any change in society, is that they did it. Sure, there are the big names. But the change came from thousands of choices and actions big and small by individuals just like us. None of us, not even our heroes, are perfect. But all of us can make change.

Why is it important to you that the NPS share all people's stories?

As a federal agency, we have a responsibility to serve all Americans, as well as our international visitors. That means sharing all people’s stories with everyone. This includes face-to-face in the parks and at our sites, but also online via what we do on social media and on nps.gov.

Being seen and represented is so incredibly important to feeling valued and welcomed. Sharing these stories also is an opportunity to create understanding and empathy between individuals with different backgrounds.

And if that doesn’t resonate with you, I will say simply that expansive history, while it may be messy and not allow for tidy stories, is good history. With over 400 sites and programs that reach into every county across the country, we have a responsibility to do good history.

Megan Springate (she/they) is an historical archeologist by training and received her PhD in Anthropology from the University of Maryland. She works in the National Park Service (NPS) Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education in Washington, D.C., and currently serves as the National Coordinator for the NPS 19th Amendment Centennial Commemoration.

*Traditional Knowledge, Indigenous Knowledge, and Local Knowledge are understandings, skills and philosophies developed by societies with long histories of interaction with their natural surroundings. For rural and indigenous peoples, local knowledge informs decision-making about fundamental aspects of day-to-day life. This knowledge is integral to a culture that also encompasses language, systems of classification, oral histories, resource use practices, social interactions, ritual, and spirituality.