Learning and Healing from Hard Truths at Natchez National Historical Park

.

.

Thanks to authors like Ta-Nehisi Coates, much of the world is living through a gravitational shift in perception: freshly seeing through the eyes of people whose vision has long gone unvalued; newly hearing the words of those who were previously silenced; and coming to realize the long-term personal suffering wrought by international and impersonal systems of oppression and financial gain.

The telling of some of America’s hard and shameful stories was hardwired into the 1988 creation of Natchez National Historical Park in Natchez, Mississippi, the first national park created by Congress with a mandate to tell the stories of “blacks, both slave and free.” It will come to full fruition as the park develops its newest historic site, the Forks of the Road, the marketplace just outside of Natchez where enslavers carried out the unimaginable practice of human trafficking.

Since 1932, Natchez has been world-renowned for its Spring Pilgrimage tours of many beautiful antebellum mansions, fulfilling tourist fantasies born during the Great Depression and fueled by the lure of a “Gone With the Wind” style of southern romanticism. It was an industry built on hospitality and theater, not historical accuracy.

The truth is that the wealth underlying the grace and charm of the town’s historic architecture was built on a horrific international system of human trafficking of people of African descent that dated back to the earliest French settlement on the bluff occupied by the indigenous Natchez tribe. After the importation of enslaved Africans to the United States was outlawed in 1808, a new pernicious system rose to take its place: an interstate, domestic human trafficking system. Thousands of families in the eastern states were torn apart for individual sale into the deep South where the profitable production of cotton and sugar guaranteed high prices for them. For many it was a death sentence. For almost all, it was the last time they saw their families.

Some people were shipped on boats to New Orleans and sold in the markets there or put on steamboats for the trip up the Mississippi River to Natchez. Others were marched chained in coffles overseen by armed drivers a thousand miles from the Atlantic westward, down through Appalachia along trails like the Natchez Trace, or from Alexandria, Virginia to Natchez, like the McQuinn family, whose story is depicted here.

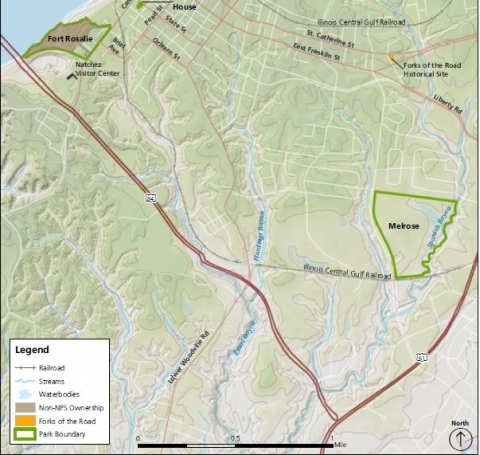

The Forks of the Road unit of Natchez National Historical Park will mark the point where people arrived at the second-largest human trafficking site in the deep South during the decades leading up to the Civil War, where they were inhumanely held and examined as merchandise, where they were sold by wealthy traders in private transactions that have left few clues for their descendants. There is no other national park that tells this story.

"There remains a disconnect, a hole in the community consciousness – in the national consciousness – that cries out to be filled."

Imagine an 18-acre site today on the northeast side of this small southern town that gives passers-by almost no indication of this history of immeasurable human tragedy. It sits nestled among a handful of large antebellum estates. It is crossed by a major road, covered with the detritus of urban intrusion, surrounded by neighborhoods and businesses – many owned or occupied by descendants of those whose lives were forever changed at the market. A rich community of black achievement and culture eventually grew up in the town around the site, including ground-breaking legislators Hiram R. Revels and John R. Lynch and novelist Richard Wright. But there remains a disconnect, a hole in the community consciousness – in the national consciousness – that cries out to be filled.

In response to years of lobbying efforts by local activist Ser Seshsh Ab Heter – CM Boxley and the Friends of the Forks of the Road Society, Inc., Congress funded a feasibility study in 2005. Once the site was deemed eligible for inclusion in Natchez National Historical Park, additional Congressional action, in the form of a boundary adjustment, was required. In 2017, Congress passed legislation (P.L. 115-31) expanding the boundary of Natchez National Historical Park, thus authorizing the NPS to acquire property associated with the Forks of the Road site. Following passage of this law, NPS worked with its key stakeholders to secure funding for land acquisition through the Land and Water Conservation Fund. The City of Natchez is supporting this effort by donating more than two acres of city-owned property within the boundary.

In 2019, the National Park Foundation started providing financial and technical assistance to the Trust for Public Land for land acquisition for the Forks of the Road project. As the National Park Service begins planning for the site, the National Park Foundation, along with other key stakeholders, is positioned to streamline this process by leveraging philanthropic funds. Without this support, the long-term impact of the site would be drastically reduced. The Archeological Conservancy and Church Hill Creative Foundation are also key partners in championing this important initiative to preserve and protect this site.

Future development of Forks of the Road site may include construction of a formal memorial, a learning center, and the preservation of the historic roadbed and bridge leading into the site. Ultimately, the Forks of the Road will take its place among other international sites of conscience in sensitively telling the most horrific truths in the service of healing and learning.

Kathleen McClain Bond is the Superintendent of Natchez National Historical Park in Mississippi.

Header image: This building, where a landowner who rented spaces to human traffickers at Forks of the Road may have once lived, remains on the site.