Labor History in National Parks

.

.

The history of a nation is a reflection of its people, a rich, interwoven tapestry full of triumphs and struggles alike. Labor history is an undercurrent of many of these stories, documenting the ways people have worked to put food on their tables, raise their families, and make a living. The labor movement, recorded and preserved in national parks across the country, stemmed from the need to protect workers’ interests, fight for better working conditions, safety, and health benefits, as well as racial and gender equality.

The National Park Foundation (NPF)’s work in history and culture helps safeguard the historic sites and collections that hold our shared history through dynamic educational programs, professional development opportunities, rehabilitation of historic sites, and the preservation or irreplaceable artifacts and places. Discover some of the stories of labor in the United States, including the labor movement, to be discovered in our national parks, and NPF’s work to support the preservation and sharing of these important pieces of our collective history.

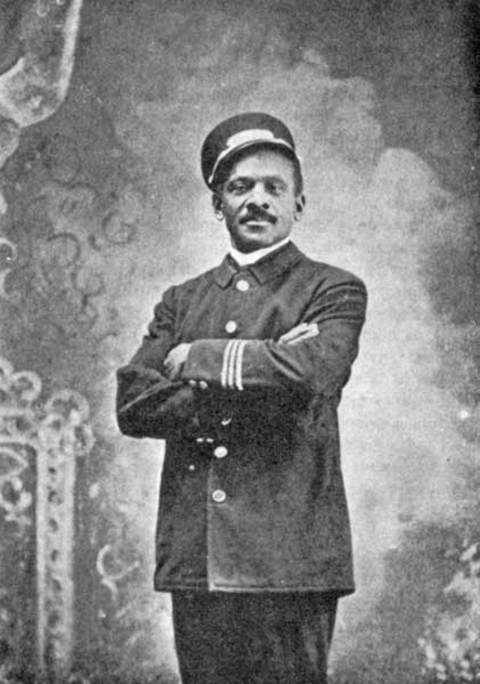

Pullman Porters

Pullman National Monument, located in Chicago, preserves the first planned model industrial community of the United States. In 1894, a nationwide boycott of handling Pullman Company train cars led to violence as soldiers were dispatched to aid local authorities. In 1925, A. Philip Randolph founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first African American labor union. At the time, porters made up 44% of the Pullman workforce, making the company the nation’s largest employer of African Americans.

BSCP wanted to improve the working conditions and treatment of African American railroad porters and maids, though the Pullman Company refused to recognize the BSCP. However, after the enactment of the New Deal – which provided some of the strongest ever protections for organized labor – the Pullman Company agreed to begin negotiating in good faith with the porters. In 1937, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the Pullman Company reached a landmark agreement – an important step for African American civil rights.

Today, the rich history of the Pullman Historic District, including the stories of the Pullman Porters, is preserved at Chicago’s Pullman National Monument. NPF has long supported the national park, providing $10 million in support of the construction of its visitor center and revitalizing the site. NPF's support, along with other partners including Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives (CNI), will construct the visitor center within the Pullman Administration Clock Tower Building, as well as make improvements to its 12-acre grounds and other historic buildings. Additionally, NPF has worked diligently with the Historic Pullman Foundation as it builds its organizational capacity to support its journey in becoming the park's official nonprofit partner.

United Farm Workers

Founded in 1962 by César E. Chávez, Dolores Huerta, Gilbert Padilla, and other labor organizers as the National Farm Workers Association, today's United Farm Workers of America (UFW) was the first enduring and largest farm workers union. For more than a century, farm workers in the fields of California and beyond were subjected to harsh conditions and were met with discrimination and violence whenever they sought fair treatment.

Chávez and other community organizers founded what would become UFW and began a burial program, a credit union, health clinics, daycare centers, and job training programs. In the 1970’s the UFW expanded to act as a national voice for poor and disenfranchised people, joining other reform movements and gaining support from millions of Americans to help improve workers' living conditions and wages. The UFW continues to champion legislative and regulatory reforms for farm workers today and the story of the UFW and one of its founders, Chávez, is preserved at César E. Chávez National Monument in California.

NPF helped support the park’s operations for its first year and in 2015, helped 130 fourth grade students travel to the park through our Open OutDoors for Kids program. A 2020 Women in Parks grant from NPF supported the research and documentation of the experiences of Mexican, Filipina, and Chicana women farm workers in California, highlighting their role in the farm workers movement.

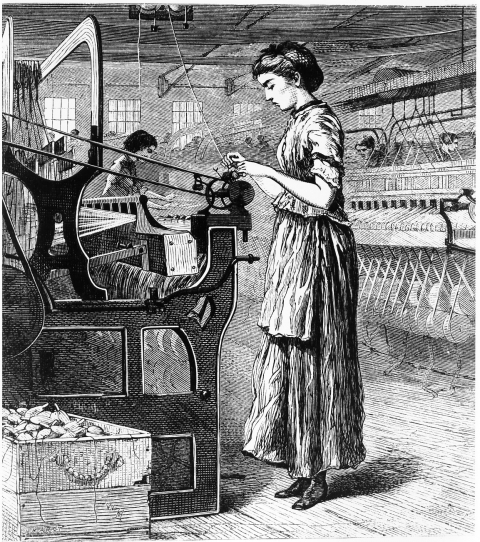

Lowell Female Labor Reform Association

Lowell, Massachusetts’ water-powered textile mills, now preserved as Lowell National Historical Park, is just one example of how the Industrial Revolution in the U.S. transformed the way we work today. Lowell’s social and economic opportunities were sought after by immigrants and young women, and workers toiled for 12-14 hours a day (and half-days on Saturdays) at the mills. While the positions at Lowell offered higher wages than in other textile cities, the work was arduous and conditions were often unhealthy.

Lowell was the site of two strikes, in 1834 and 1836 respectively, organized chiefly by women who saw reduced wages and poor conditions as threats to their economic independence. In December 1844, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association (LFLRA) was founded to advance the interest of Lowell’s female workforce at the state level. The LFLRA collaborated with other local labor groups and supported the 10-hour movement, advocating for the passage of regulation so corporations could only have workers on the job a maximum of 10 hours a day. Without the right to vote, LFLRA's members effectively used petitions to show legislators how many people supported their cause.

Many of the women who participated in these strikes learned to rally support of their communities and used these skills in support of other causes, including antislavery and women’s rights. NPF’s Women in Parks initiative supports programs and projects that help national parks share a more comprehensive and inclusive American narrative that amplifies the voices of women who have changed our nation, like the women-turned-organizers who worked for better working conditions at Lowell.

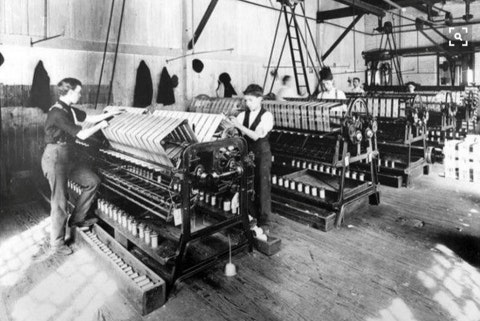

Workers in Silk City

Paterson, New Jersey may have been designed as America’s first industrial city by none other than Alexander Hamilton, but it was nearly a century after the foundation of his Society for Establishing Usefull Manufactures (S.U.M.) that Paterson really hit its stride. Paterson churned out a diverse range of items, from cotton and wool textiles to railroad locomotives and firearms, attracting immigrants from Ireland, England, Russia, France, Germany, Poland, and other parts of the world where people were looking for new opportunities. After the Civil War, Paterson’s silk manufacturing boomed and by the 1880s, the city was producing almost half of the silk manufactured in the U.S., earning its reputation as the “Silk City.”

In January 1913, broad-silk workers triggered a strike that became notable for its unity of participants of many different nationalities and crafts. Dye house workers and ribbon weavers soon joined the cause, and before long the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) union helped organize a central strike committee to unite the various craft and ethnic groups. By February, nearly 300 mills and dye houses were closed as 24,000 men, women, and children (workers as young as 14 were working 11-hour shifts) joined an industry-wide strike. The demands of the strikers were multi-faceted, seeking wage increases for certain positions, an end to newly imposed systems in broad silk and ribbon weaving, and an eight-hour workday.

The six-month strike was ultimately unsuccessful, but the strike focused national attention to the plight of mill workers, eventually contributing to nationwide improvements of working conditions, including the end of child labor. Today the complicated history of Paterson is preserved at Paterson Great Falls National Historical Park, where visitors can tour the historic mill and learn other stories. NPF’s support of the NPS Mellon Humanities Fellowship program helps expand storytelling at national parks through scholarship, including labor history stories in parks such as Great Paterson Falls.

National parks are a wonderful resource to discover more about our past, reflect on our present, and imagine our future. These are just a few of the labor histories that our national parks preserve. NPS and NPF are working to expand storytelling at parks to share a more comprehensive history of the U.S., including the contributions and stories of forced laborers, enslaved people, and advocates of the labor movement so we can all gain a greater understanding of the park’s history. The histories of work and working people help us explore the lives of a broader range of individuals – each with their own labor history to share – and invite us to imagine a better future. Next time you're at a national park, reflect on the labor history stories that are tied to that place; be it a historic mill or a preserved landscape, each national park has a labor history to share.